First ceremony in Sete Estrellas

Chapter 9: With just a few days left of preparation before the dieta, Luis decided it was time to give me my Yawanawá name. Most of the Yawanawá have two names: a Portuguese name and a name in...

With just a few days left of preparation before the dieta, Luis decided it was time to give me my Yawanawá name. Most people of the tribe have two names: a Portuguese name and a name in their native language, Yawanawá. To feel into my name, Luis went on a long walk one evening, and when he returned, he sat down on the floor in his living room. We all gathered around him, and there in the shimmer of a few candles I received my Yawanawá name: Vāta Txanu.

That night, Luis told us a story of how the medicines were birthed into life (the story of Puyeihuninhu that I told in a precious Musing), and in that story there appeared Vāta Txanu (pronounced vah-tah-cha-new). Luis was a master storyteller. Whenever he began, people would gather around to listen to his ancient stories of their traditions, their culture. It was always a very special moment. Looking me deeply in the eyes, Luis told me that Vāta Txanu was the name he was giving me.

After Luis told his story, many people in the village congratulated me on my new name, speaking of their honour for the name. That sense of honour was something I saw many times among the Yawanawá. They often celebrated each other, speaking of the virtues of a person, honouring each other’s strengths, speaking about the good things they had done, remembering beautiful moments that had happened with them, really putting into words the good qualities of one another. That expression of gratitude was a special thing to witness, and that night, in particular, was very special for me as I received those words from the people.

A week after our return from Tarauacá, it was time to move to the jungle house. That morning, as always, I bathed in the river. It had taken me a while to feel comfortable with bathing since I thought that the river was full of water snakes, sting rays, and piranhas. The children were always in the water, playing and swimming. Everyone in the village assured me it was completely safe to swim and bathe there. On this particular morning, the water levels were extremely high from the intense rainfall in recent days. The water had come right up to the edge of Luis’s house—at least three meters higher than when I first arrived in the village.

That morning, I stood in the water near Edi’s wife, who was washing clothes. A layer of fog hung over the water and surrounded the trees on the shore; the sunlight shone through the fog. It was just magical to witness the beauty of the jungle. All at once, I heard a sound I had not heard before. I looked around but could not determine the source. Edi’s wife pointed calmly to something in the water. I turned my head and I caught a glimpse of a fin. Could that be right? I looked again and then I saw them clearly: dolphins! Two Amazonian river dolphins were playfully swimming just in front of me. I had never seen dolphins in the wild. I had heard that dolphins are seen as signs of good luck and protection. Seeing them swim put a huge smile on my face, and I jumped and yelped like a boy. The people who saw me all laughed and shared in my joy. I learned later that it is very rare to see river dolphins in the Rio Gregório, as the water levels are normally too shallow. I perceived those two dolphins as a very good sign for our dieta to start, full of protection and confirmation that all was happening in divine timing.

A short while later, we moved into the jungle. While I unpacked my things, Edi and Muca made a provisional kitchen in front of the house. In just an hour they erected a small structure using sticks, some vines, and a few palm leaves. I cheered them on and felt it was a blessing to have those two in the dieta.

When we were all set and comfortable, the sun started to set. We put our hammocks on the porch. I encircled mine with a mosquito net that made me feel like I was in a palace. I have always loved hammocks. That night, we held our first ceremony and drank the Santo Daime for the first time.

While we were putting our hammocks up, I heard some noises coming from the jungle, listening more closely they sounded like footsteps. I looked down the path and saw a flashlight appearing in the darkness of the trees. I was confused. Hadn’t we agreed that there wouldn’t be any more people? In a heartbeat, my doubts from a few days back had returned.

One of the people approaching was Maku, a young man from the village. He emerged from the dark with the flashlight and a guitar, wearing a crown of white feathers. He looked magical. “Pajé original,” Luis said, meaning “original shaman.” The other boy was Maku’s visiting cousin Mana, who was in the village for fifteen days to take flower baths that would help him become a better hunter.

The jungle was full of surprises! I didn’t really know what to do. If I voiced my concern that we had a clear agreement about this, the positive vibes of the moment would evaporate. It felt really special to have a first ceremony happen since arriving in the jungle. So I just let it all happen.

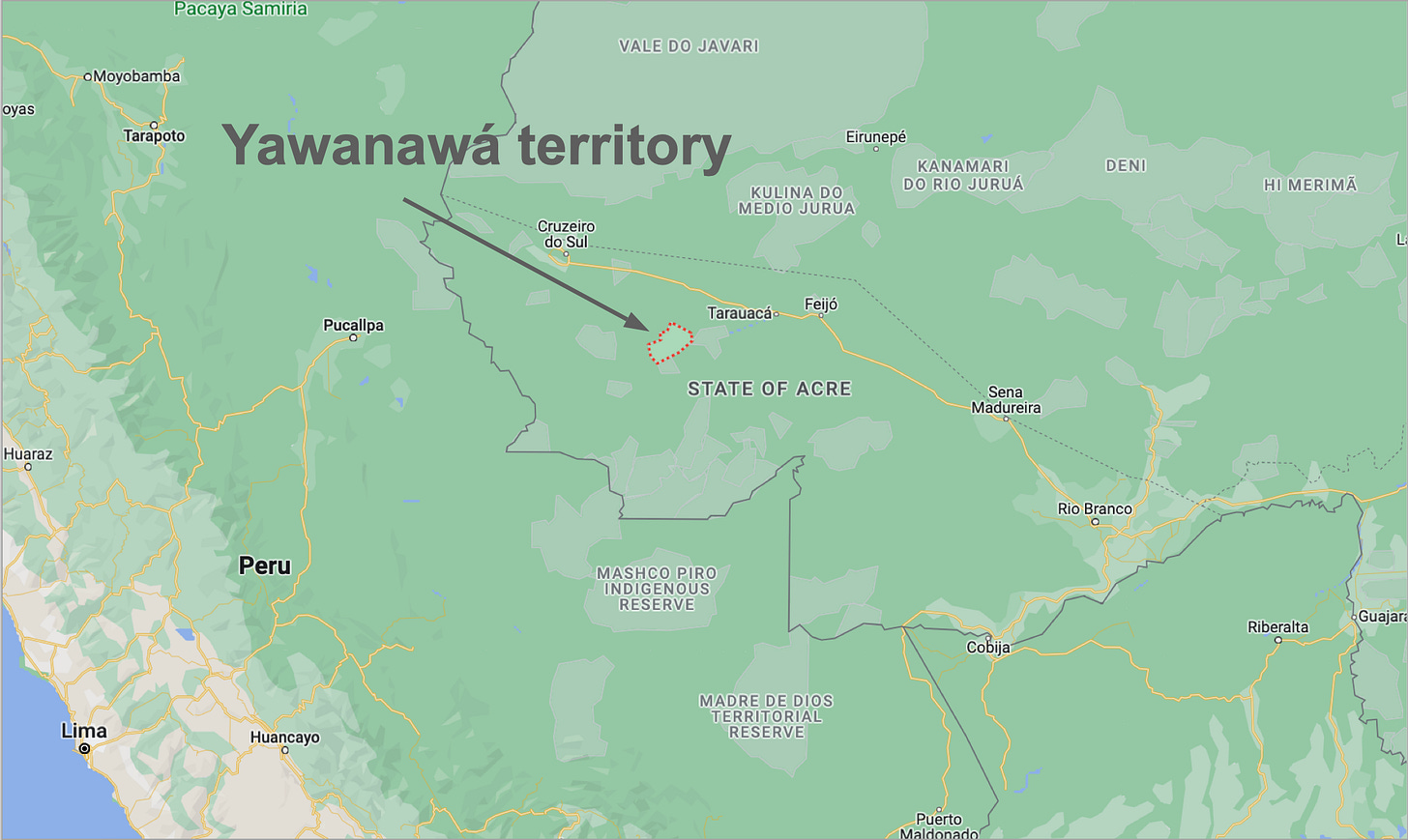

Most of the people in Sete Estrellas hadn’t drank Medicine for a while. In the 60’s the New Tribes Mission of Brazil (MTB) came to try to ‘evangelise’ the Yawanawá community and introduce new Western customs. The missionaries basically forbade the tribe to use their traditional Medicines, speak their language, drink Uni and be in their ceremonies. During this time, most Yawanawá lost the connection with their spirituality; only a few held that sacred wisdom alive. In 1983 the Yawanawá agreed with the missionaries for them to leave their territory. Soon after that, the ancestral land of the Yawanawá community was legally marked out by the Brazilian government; an area of 92,860 hectares. At that time the dieta of Muká hadn’t happened for a good few decades. In 2008 more land was added and marked as part of the Yawanawá Indigenous territory.

Somewhere around the turn of the Millennia, 3 young men of the tribe entered the dieta of Muká: Bira Yawanawá, Matsini Yawanawá and Tio Nani. That dieta of Muká was a very important moment; it might have been the start of the rebirth of the Yawanawá culture.

Since then the spirituality had slowly begun to come back, especially in the villages of Nova Esperanza and Mutum. In some of the other villages, like Sete Estrellas, it hadn’t fully come back yet, and moments of people drinking Uni were rare. In Sete Estrellas, people hadn’t drank Medicine for a long time when I arrived. So when we sat down to start our ceremony, it felt natural to all that I would be leading this ceremony. Luis didn’t drink Medicine, but he was present, always watching me. After saying the opening words of the ceremony, I served the medicine to the others. We sat in our hammocks, which were hanging close to each other. It felt cosy on that porch with Edi, Muca, Maku, and Mana around. Luis sat at a distance, between two trees, balancing in his hammock. I had no idea how this ceremony would unfold. In the ceremonies I had participated in or led, there was always a “noble silence,” which means there is no speaking, no talking, no sharing. I wondered whether it would be the same here. But from the moment the ceremony began, silence was off the table. We laughed, talked, and sang. Everyone spoke about each other, honouring each other: “There is Muca, the great warrior. Such a strong man, such a radiant soul, on the edge of eating the plant that carries the same name: Muka. He is going to be a strong pajé, a strong leader of his village. Later he will have many wives and many children to celebrate his life.” And after that, we all said a big long “IIIIHUUUUUUUUUUUU.”

Like this, we continued for everyone. Hearing all those words made me feel so good. I was drinking medicine with the Yawanawá in Sete Estrellas. It felt magical, it felt sacred, it felt right. What a journey it had already been to get here, and this was just the beginning! This way of speaking I encountered many times in the tribe since. I find it really special to hear so much acknowledgement being spoken from one person to another.

In the ceremony, they also told stories: ancient stories, stories about the plants, stories about the animals, and stories about the medicines they were using. After an hour or so I started to sing. I took my guitar and sang from the heart:

From deep within the mother Gaia

And reaching out, to the father Sun

I am so grateful for this life

And to be serving

The will of the One

Om Hari Om

When I sang these words, tears of gratitude and grace ran down my cheeks. The words resonated so strongly with me. Songs were guiding me all the time—singing was my prayer.

After every song we would all shout together, expressing our joy and elation:

IIIIIIIHUUUUUUUU!

I couldn’t stop laughing during that ceremony. I was rolling in my hammock, laughing it all out. So many things were coming up for me, so many situations and conversations that had happened in the past, the ended relationship with my girlfriend, the hardship of leaving the orchestra world, challenges that had happened in the centre in Peru, all the judgements of people about my path with the medicine: I just laughed them out. I wasn’t laughing at them. I was just seeing the bigger picture, seeing how we all can get caught up in our own little worlds. The previous months of my life, which had been quite challenging, were all coming out of me in deep laughter. It felt so amazing to release all those things lying in the hammock, deep in the jungle.

After that first ceremony, in the middle of the night, Luis came to me and said, “Vāta Txanu, you know Uni.” Uni is what they call Ayahuasca in their native language. You know the medicine and how to work with it. You have a strong connection with her. From now on, you will lead all the ceremonies with Uni when you are here. You have the spirit of Ayahuasca inside of you. She speaks through you, she sings through you, she lives through you. I honour you for the work that you do with her. Thank you for coming to us.”

The three others were standing around me when this happened, and they looked at me with admiration and hugged me. “You are a strong warrior,” they said. “When Luis says something like this, it is true. You have the spirit of her inside.” As they said these words, they each raised a fist in the air and shouted, “Strong warrior!”

IIIIIIIHUUUUUUUU!

That first night was just amazing, full of joy, sacredness, and so much laughter. It was a beautiful start to our time in the jungle together. If the next three months are going to be like this, I thought, then it is going to be beyond my imagination…

The next day, we woke up in our hammocks after just a couple of hours of light sleep. Louisa made us some breakfast, and we bathed in the tiny stream close to our house. This would be a special morning: we would go look for the Muka plant to open our dieta.

Muca and Edi took some rapé, and then we walked into the jungle. We were looking for a very small plant, one virtually unknown to the Western world. It has no Latin name yet; it has been kept sacred and secret for a long time. I had no idea what to look for, so I just walked along, hoping that one of the others would find it. Everyone was looking with full attention.

We walked for hours, but we didn’t find any Muka. I got a bit impatient, and the Indians could feel my tension. After about four hours, Luis announced that we would stop the search. The next day we would continue in a different part of the jungle. A wave of disappointment hit me when he spoke those words. We could all feel the tension and disappointment. That night we didn’t speak much, ate our food and sat around on the porch of the jungle house.

That evening we had rapé, the fine powder made from tobacco and the bark of a tree they call “txūnu.” The first time I had taken rapé was on the porch of Luis’s house, sixteen months earlier. I had puked for at least an hour. During that time, almost the whole village had walked by. Some of them would ask, “Rapé?” Luis would nod, and the people would walk on as if it were completely normal to have a two-meter-tall white Dutch guy puking his guts out on a porch in their village.

I learned that the people of the Amazon have a completely different way of looking at puking than we Westerners. When a person feels sick in the Amazon, someone goes into the jungle and finds a plant to help them with purging. If something bad is inside of the body, it’s good to get it out, I hear some of them say. That night I received rapé for the second time, and although I hadn’t liked it the first time, I was committed to this dieta, and accepted this as being part of it. The rapé hit me hard that second time as well, but at the same time, something interesting happened.

The spirit of rapé spoke to me. It gave me an understanding of what was happening. It focused my mind, stopped the mental noise, and cleaned my body in a way I had not experienced before. The disappointment I felt after not finding the Muka started to disappear, and greater understanding came in. To enter such a strong process as the dieta of Muka, I had to be prepared and patient. How could I enter such a deep journey that would most probably have an effect on the rest of my life, and not be willing to wait for a few days for the right moment to happen? My body and mind relaxed into that understanding. It was a truly humbling moment.

In the next few days, I slowly got used to rapé, which they gave me every day. I threw up after every time they blew the fine powder into my nose, but slowly I grew accustomed to it. The men of the village would take rapé many times a day, even the small boys. I never saw any women take it during my dieta of Muka; at that time, it seemed to be a medicine that belonged to men.

Thank you for sharing your story. "The spirit of rapé spoke to me." — this line is exactly what I love to fell in rumē. Never forget how it heppend for the first time — at the moment whe I recieved my tepi my relations with tobacco totally changed. From that time I started to hear it. Being honest not every time. But every exact time I really need to hear something. Rua pa. Viva Yawanawa!