Breaking into Tibet

Chapter 2: Since I was young, two things have always been very present: healing and music. Music has been a presence in my life since I was born. During my childhood...

Voice note around Tibetan Sky Burial

Since I was young, two things have always been very present: healing and music. Music has been a presence in my life since I was born. During my childhood in the Netherlands, my mother played the radio for me, surrounding me with music from all over the world. She hummed and sang to me, and from an early age, I joined in. The vibrations soothed me, and music came naturally to me. From early on I knew that music was in my future. Music has always been my most natural language for communicating. And looking back, music has been a bridge between the material and spiritual realms for me.

I began music lessons when I was six, starting with the recorder. I was a quick student and excelled in my class. A year later I began playing the flugelhorn, a kind of trumpet. My father would often tag along to the music lessons and stand right next to me as I practiced, helping me in many ways. I went on my first international tour when I was twelve. It was exciting to travel abroad without my parents, and as the youngest member, I was taken under the conductor’s wing. We travelled for weeks in Italy, and he taught me many things about music. Walking through the cathedral of Venice, I learned about the physics of sound. In many ancient places, he explained about the history of music, and so many other things. I treasure those lessons in my heart to this day.

When I was eighteen, I moved to The Hague, studying bassoon at the Royal School of Music. It was great to be studying together with so many other talented musicians from all over the world. In those years I heard the Concertgebouw Orchestra for the very first time in Amsterdam. I was inspired by their music and passion. It was a childhood dream of mine to play with that orchestra one day.

It was during my early studies that my journey as a healer began. I received my first initiation into Reiki, a kind of energy healing, from a woman who held weekly meetings for healers. For several years I attended her meetings and learned about different modalities of healing and spirituality. There were group healings, studies of the energies of crystals, and we practiced different methods of energetic healing. It was there that I learned for the first time about reincarnation.

I had sensed from a young age that there was more in life than just what I could see with my eyes and touch with my hands. I was strongly drawn to these new ways of understanding things. It was a time of great learning for me, progressing in my music at the Royal School and learning about healing and spirituality in those weekly meetings. But while the meetings were an important part of my life, not many people knew I was part of them. I kept them separate from my life as a musician.

During those years of study, I continued touring during the summers with an international youth orchestra. One summer we played “Parsifal,” an opera by Richard Wagner. Claudio Abbado, a living legend, conducted the orchestra. It had been an honor to work with him for several weeks in a row. With a full orchestra of young, talented musicians from all over the world, we had travelled in luxury and stayed in some of the best hotels.

After four years of study, I was preparing for my final exams in June, 2003. I planned to continue my studies in Berlin with a grandmaster of the bassoon, Klaus Thunemann. My classes would start in the beginning of October. I began thinking about the four months of freedom I had before this new chapter of studies would begin. I wanted a break from music and from playing the bassoon. I wanted something completely different. I started to think, “Where am I going? What do I want to see? Where do I want to travel?”

Touring with the orchestras, I had seen much of Europe and travelled to Japan and northern parts of Africa. This time I wanted to go to a place where I could learn something different, where I could experience something new, and meet other kinds of people. I wanted a shift from what I had already seen. And I began wondering to myself, where should I go? Much of what I had been studying in my free time was birthed in the Far East and I felt drawn to some of the ancient practices that originated there, like meditation and yoga. I had not really tapped into these things yet, but they were pulling on me strongly. Something was calling me. Feeling into that question, two destinations came to me: India or Tibet.

I began asking around, and my cousin connected me with a friend of hers, a real adventurer who had traveled to many places for years. When I asked her about India, she said that India is crazy. “If that’s going be your first travel to the East …” she said, her voice trailing off uncertainly. She told me it would be mind-blowing, that it would be too overwhelming. “Don’t do that,” she said. “It’s too much. Go to a place that’s easier, more accessible. Go somewhere you can learn how to travel, and then afterwards go to India.”

And when I heard that, I thought, “Yeah, good.” It felt right to me. I asked her where she had been, what places she could recommend.

She began telling me about Nepal, the tigers she saw there in the wild, the incredible trails she had hiked in the massive, Himalayan mountains, and Katmandu, a magical city full of temples, with gentle, open people. She told me enthusiastically about the people she had met, and how easy it was to meet other travelers. The way she spoke, I felt sure this was what I wanted to do. And I asked her, “Have you been to Tibet?”

“No, I didn’t go there,” she said. “It’s difficult to get into Tibet because of Chinese communist entry restrictions, but if you’re in Katmandu, then you’re in a good place to find an entry. Officially you can only enter Tibet with a group and a group visa, but—”, she paused, “some people will help you. Spend some time looking, have some cash, and you can find a way.”

Those last words gave me the final nudge. I knew that my next destination would be Tibet, the roof of the world. A country with tales of magic, ancient wisdom, and people with open hearts and an incredible, deep spirituality. China invaded Tibet and nearly destroyed its culture. The world had let the destruction happen.

It was said that the last remnants of ancient Tibet were rapidly disappearing, so felt an urge to visit the country, to be able to catch any glimpse of the old I could find. I regretted that I never went to Berlin when the wall fell, that I was not there at that magical moment of a shift in human history. I had seen how it had changed Berlin and Germany. Maybe Tibet is the same, I thought. There were plans to build a train which would open up immigration, bringing in a flood of Chinese people so that China could take over still more of Tibet, destroying its culture in another way, more slowly but more steadily.

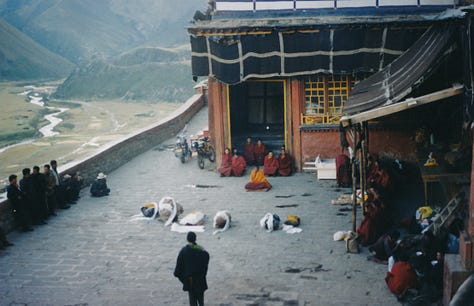

I read about Lhasa, with the palace of the Dalai Lama, the Potala Palace. I read myths about Mount Kailash, one of the most sacred mountains on the planet, where Mother Ganga (the Ganges) and three other major rivers are birthed. I saw pictures of the turquoise Himalayan lakes, the yaks in the snow, and beautiful, gentle, open-hearted people with big eyes and genuine smiles. I wanted to meet those gentle people, walking with their prayer wheels. Some of them would bind pieces of wood to their knees and elbows and travel for hundreds and hundreds of kilometers, prostrating themselves on the ground every third step for weeks, months, or even years to get to the Jokhang temple, and then stay there, pray, and receive the blessings from that place.

Where in the world can you find this? I thought to myself. A completely different culture, and one on the edge of extinction. To get a glimpse of that! I felt that I needed to go, that time was short.

I began planning my trip. I would fly to Katmandu, the capital of Nepal, and from there I would find a way into Tibet. I would travel for two months, and work for six weeks beforehand to make money for my trip. I could get work at a laundry factory that was close to my parents, which specialized in cleaning linens from local hotels and hospitals. I had already worked there several summers to earn a bit of money, so I had good connections there.

One weekend, a few months before summer, I went to stay with my parents to tell them about my plan. It was always nice to take a break from my studies in The Hague and spend time back home. Saturday evening we sat down at the table for dinner, and I broached the subject slowly.

“This summer I decided not to go on tour with the orchestra,” I started. “I think instead I want to go on a holiday.”

“Oh, how nice,” my mother said encouragingly.

My father asked, “What kind of holiday are you thinking of? Where are you going?”

“I want to travel two months through Nepal, and see if I can get into Tibet,” I said.

Those words were the overture of a long silence at the table. My mother’s face turned cold. She looked at me in fear. I could sense that something was boiling up inside of my father.

My mom wanted to say something, but she was holding back. After a few minutes she burst out: “Why do you want to go to these kind of places? You always want to do something different. Can’t you just go to a normal place? To a place where all people go?”

“It’s dangerous there,” my father joined in. “A Third World country. You have no connections there and you want to go all by yourself?” He looked at me sternly. “How can you do something like that? You always have these ideas to be different. Go to a normal place!” There was anger in his voice, and I could feel tension and fear in both of them.

They kept talking, and as their words continued, I felt sad and upset. It was clear that they would need more time to understand what was happening. At the same time, I knew that they would eventually support my plan.

I tried to make them see how special a time this was, and why I wanted to do something different. “I have this time now. When do I have a summer where I have three, four months free? I can work a bit, earn some money, and then just go and be free and see these places! And this will be after my final exam, after finishing my bachelor’s degree and before beginning a whole new chapter of studying for my master’s in Berlin.”

My parents were quiet. The tension at the table was palpable.

I spoke slowly, carefully. “I understand and hear that it’s not your choice, and that you wouldn’t go there,” I said to them. “But I’m going.” I let my statement hang in the air for a moment.

“I’m going there,” I repeated. “I’m going to see what’s there and find out what it is. It’s calling me, I don’t know why, but it is. Maybe in a few years, Tibet will be not so special anymore. I don’t want to go years from now when everyone else is going, when it becomes just a tourist attraction and a kind of Disneyland. I would like to see it now, while it’s still authentic, and meet those people.”

The rest of the dinner was silent. In the weeks that followed, my parents continued trying to change my mind, to no avail. I started work at the factory, looked for tickets to Katmandu, and began reading up on Nepal and Tibet. The more I learned about those countries, the more I relaxed into my decision. Tibet was calling, and I had to listen and find out what was there for me.

A few weeks later I was on a plane to Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. I planned to stay at the Katmandu Guest House in the middle of the old city, a popular hostel where I could easily meet other travelers. I had read that rooms were about two dollars a night for a simple, single room with a shared shower down the hall. I brought a sleeping bag, as I had read that the sheets were not super clean, or even changed for every new person that came.

Looking out the window when the plane was close to landing, I saw beautiful, green, round hills and quaint, tiny villages. In the distance, snow-packed peaks pierced the sky. The atmosphere in the airport was laid-back. The guy at the counter had a huge smile, and the first thing he said was, “Welcome to Nepal!” What a change from the usual grim-faced border-control people I had encountered at other airports. I was through customs in a breeze.

Outside, many cab drivers tried to pull me in their direction. Soon I was seated in a taxi, explaining that I wanted to go to the Katmandu Guest House. We pulled away from the curb and almost immediately swerved to avoid another car. My driver honked and forced us into the merging traffic. That shocked me, and I sat petrified in my seat. Traffic got worse, and he swerved again, leaning on the car horn. I had never seen such chaos on a road. We were surrounded by cars, and every one of them seemed to be driving totally out of control. It seemed that where Western drivers would hit the brake, Nepali drivers would lay on the horn. I held onto the back seat tightly, expecting a collision at any moment.

The taxi driver spoke to me over his shoulder, saying in English, “Don’t worry, sir, nothing is going to happen.” His reassuring tone, and his big smile, contrasted starkly with the chaos around us.

Magically, nothing happened, and all the while my driver talked to me calmly in the midst of the noise and commotion. I learned that he wasn’t taking me to the Katmandu Guest House after all. “No, no, the guest house is full!” he said. “You can’t go there. I will bring you to the hostel of a friend. Very good, very close, and much cheaper.”

I had read about taxi drivers in Nepal, and how they would try to take you somewhere else where they would receive a commission from the facility. “No, it’s not full, I made a reservation,” I said with as much certainty as I could muster at the moment. The truth was, I had not made a reservation at all.

He insisted that he could not take me. “Didn’t you hear me? The Katmandu Guest is full!”

But I stayed firm. “No, please take me to the Katmandu Guest House. I won’t go anywhere else.”

With a lot of reluctance, and after driving me around and stopping at two other places, he finally dropped me at the Katmandu Guest House. I had learned that they didn’t give commissions there, so it was not a popular place for taxi drivers. Perhaps because he had run up the bill by all that driving around to places I didn’t want to go, the driver took off in good spirits after I paid him. It had been such a wild ride, and it took me a minute to collect myself.

I walked into the guest house, and the first thing I saw was a guy sitting on the terrace with a tee-shirt reading: “Ik ben toch zeker van Eindhoven!” (I’m proudly from Eindhoven!) That put a huge smile on my face: Eindhoven is a city in my homeland.

“Hey, you’re from Eindhoven!” I said.

“Of course,” he said, in Dutch. “Otherwise I would not be wearing this shirt.”

When I told him I had just arrived in Nepal, he invited me to go touring with him and his friends through the valley. They were planning to visit local temples and villages.

“I would love to join you!” I said. A history teacher in his late thirties, he had read an incredible amount about Nepal and proved to be an amazing travel buddy. At one point I told him I wanted to go to Tibet.

“That’s really difficult,” he said. “Many people come to Katmandu with that wish, but not many actually make it. But maybe if you look around you can find the right people.”

“Where do I look around?” I asked.

“Go to all the travel agencies and talk with people,” he said. “Post papers on the notice boards, and look at notice boards because other people might also want to get there. You probably won’t get a visa by yourself. That’s very difficult and expensive. But with a group, who knows? You seem to be a smart guy who knows what he wants and gets what he wants, so go for it.”

I spent a few days going from one travel agency to another, talking to people, browsing the notice boards all over Kathmandu, and telling everybody I met that I wanted to go to Tibet. “Do you know a way into Tibet?” I asked over and over again. Many times I ended up in a long conversation, but the usual answer was usually, “No, it’s not possible.” Sometimes I was told “We don’t have a date now, come back in a few days,” or “Our group is already full,” or “It’s very difficult to get a visa.”

After many days and many disappointments later, I was still determined to find a way into Tibet. “Whatever happens, “ I told myself, “I’m going to do it, even if I have to cross the border walking through the mountains.” Nothing was going to stop me.

One night in a bar, I met a guy in his fifties. He had a British accent. He looked very relaxed and had a big smile on his face. He was telling some other travelers about his trips to Tibet, and when I heard him speak, I sat down next to him. He had been to Tibet six or seven times.

“How do you get there?” I asked him.

He was quite forthcoming, even though his answer sounded vague. “I know this Tibetan guy,” he said. “He’ll meet you at the border, will prepare your visa, and will take you through the country and show you all the places. You have to go with a group of about ten people in a minivan that will drive you all the way to Lhasa. If you want, I can connect you. He has a friend here that will bring you to the border, and from there, this other guy will take you.”

“I would love to be connected,” I said.

The next day I went with him to a travel agency in a tiny back alley in a part of Katmandu where I had not been yet. I would never have found that place by myself. He introduced me to a guy in the travel agency, and left.

The agency questioned me about my plans for a very long time. But in the end they said “Yes, we can take you to Tibet. We can leave in a couple of days. We just need a few more people. You might be able to help us find some, and when we have ten people, we can go.”

They already had six people signed up, so I went out and talked to other travelers about joining us. Surprisingly, I didn’t get many positive reactions; it seemed that not many people were as anxious to go to Tibet as I was. Luckily the travel agency found some more people, and a few days later I got a notice that we would leave the next morning.

We had to be at the agency at five in the morning. From that moment on, we would be in a minivan for four or five days straight, driving through the mountains over really bad roads. With my height of almost two meters, I really wanted to get one of the spaces in front with some more legroom. If I ended up somewhere in the back, it would become a very challenging trip.

Knowing that, I had gotten up super early, packed my bags, and walked to our meeting place an hour early. When the van pulled up, I put my backpack on one of the front seats and was happy that I had secured it.

After a while the travel agency people came around to check our passports. When I opened my backpack, I looked everywhere, but it wasn’t there. Then I remembered: I’d left my passport in the guest house! My heart skipped a beat.

I jumped up, leaving my backpack on the van seat with all my money in it, and ran as fast as I could back to the hostel. It was a long, fifteen-minute run. When I got there, I rushed up to my old room, and in a drawer next to the bed, found my passport. I breathed a sigh of relief, then raced back to the van, where I found the travel guide freaking out.

“You just left all your papers and all your money here?” he cried. “What are you doing? This is Katmandu! Are you crazy? Your backpack could have been stolen!”

I didn’t know what to say. I was out of breath and speechless. I looked at my seat, and luckily my bag was there exactly as I had left it. I apologized, gave the guy my passport, and sat down in my spot. A few minutes a later, they closed the door and we left. I was sitting in the front of the van, feeling my heart beating in my chest, still grasping for air, sweating and full of adrenaline. “Wow,” I thought, “I made it!”

Once we were outside of Kathmandu, we drove steadily upward, and the beautiful lush, green valley started to shift into a different kind of landscape. Deciduous trees made space for tall pines, and we came closer and closer to the snow-peaked mountains.

In the late afternoon, we arrived at the border in a little village called Kodari. There, something ironically called “the friendship bridge” connects Nepal’s border with Tibet’s. It is easy to cross physically. The problem comes in having the paperwork the communists require to get in.

Why were the Chinese communists so opposed to tourists? I believe because they wanted to hide from the world the destruction they caused to Tibet. Today it’s easier to get into the country than at the time I attempted it, but tourists today can only visit certain spots. Those places are like Disneylands, with a very fake feel. They are not the genuine Tibet and present a false image.

We were met at the border by the Tibetan guy that the older Englishman had talked about. We took our backpacks from the van, walked over the friendship bridge into Tibet, crossed through customs, and got into another van that was waiting for us on the Tibetan side. Once we were all settled, the van slowly started to move. My body was tingling. I felt super exited. It was a dream come true.

In a single day we climbed to an altitude of over four-thousand meters, the aggressive Himalayan peaks towering around us. In a few hours we all felt really sick from the altitude. It was a wild ride, but I was so happy to be there in that van. Most of the time I was silent, listening to the other travelers talking about their wild ideas of escaping the group and going onward by themselves. As we had only a group visa, we were supposed to stay together all the time. Our guide had taken our passports and told us that we would get them back on the way out to Nepal. He wanted to make sure none of us would leave the group and go off by ourselves. As a tour guide, he was responsible for us and could get in big trouble if one of us escaped. He guarded us every step of the way, making sure we didn’t go off on our own.

The visa rules of the Chinese government were very strict, and traveling into Tibet without an official Chinese travel guide was forbidden. It was very dangerous to travel through Tibet without a proper visa. There were stories of people who had spent time in Chinese jails for doing just that.

After four days in the van, and stopping at some sites along the way, we finally arrived in Lhasa, the legendary Tibetan capital. The landscape had been mind-blowingly beautiful, but the trip had been hard on our bodies. It was difficult to breathe and walk at the same time because of the altitude, and we hadn’t slept a lot. Most everyone had vomited several times during the ride, and the last two days the van had been quiet. When we finally stopped at our hotel in Lhasa, we were all utterly exhausted.

When we lined up at the hotel to check in, our travel guide handed us our passports. We would have to hand them back as soon as the check-in was completed. I stood last in line, looking at my passport, knowing this was a moment of opportunity. I looked up, and my eyes met the gaze of an English/Malasian guy who had been silent in the van for the whole journey. It was if we were reading each other’s minds. We glanced around the room and saw that everyone else was busy with the check-in. Silently we turned and walked away.

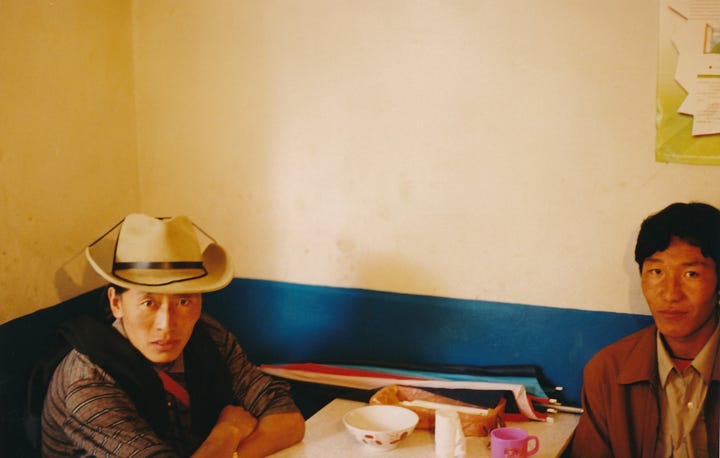

As soon as we were around the corner, we started to run. It was difficult to run in the thin air, and we were already exhausted. But we kept running with all that we had until we arrived at an older part of the town. Finally, we slowed down. Outside a restaurant, a woman saw us running and waved to us. We had no clue what we were doing, but when we saw her waving, we looked at each other, nodded, and ran toward her. That’s how we found our first refuge in Tibet.

The woman who let us into her house must have felt intuitively what the situation was, and let us sleep on the hard sofas in the room behind her kitchen. Staying with her was the first profound experience I had in Tibet, and it has always stayed with me. The Chinese had invaded her homeland, killing and torturing Tibetans, bringing in alcohol, militarizing Lhasa and other peaceful areas, and giving jobs of locals to Chinese “immigrants.” This woman had seen so much. Yet here she was: calm, happy, and serene, working diligently in silence, taking care of us so well out of the goodness of her heart. I felt great respect and admiration.

A few days later we carefully left the woman’s house and found a place to rent two motorbikes for six weeks. A few hours later we drove out of Lhasa and into the vast Tibetan plateau. Neither of us had driven a motorbike before, but after a few hours we felt like kings of the road.

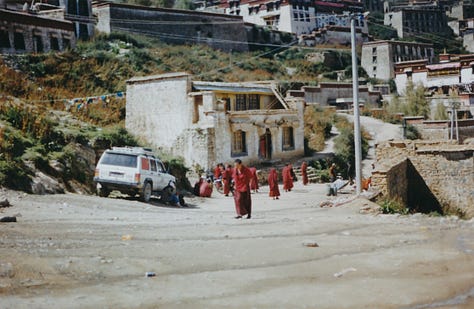

What followed was an epic trip that took us to many monasteries, through spectacular landscapes, and meetings with very special and humble people. For two weeks we had a couple of Tibetan nuns traveling with us on the backseats of our bikes. They showed us many sacred sites that we would have never found alone, and one of them introduced me to my first meditation. I had never given much thought to meditation, but once I started to connect with it, I felt it was something I would carry with me for the rest of my life.

Six weeks later, just before re-entering Lhasa, we were stopped by the police. We had been fortunate not to come across any police during our weeks of travel. When the police saw our passports, they immediately took us to the Lhasa police station. They separated us and began interrogating us. The officer that questioned me was rude and aggressive and kept shouting at me in Chinese. After several hours I broke down in tears, and then a new guy came in who spoke perfect English. Scared and exhausted, I told him exactly what had happened over the past six weeks.

After twenty-four hours in a tiny cell in Lhasa, we were released to return to the border, out of Tibet and back into Nepal. We felt quite heavy on the trip back; our encounter with the police had shaken us up. After a day of driving in silence, our driver stopped the car and pointed out the window. My buddy and I got out of the car to take a leak. I looked at the ground, feeling dejected from our recent experience.

When I looked up, I saw that we were standing in front of a majestic view of the Himalayan Mountains. Everywhere up to the vast, distant horizon, majestic snow-peaked giants stood before us. The sky was light blue, and the sun illuminated the whole mountain range. And there in the middle stood the king of them all, a snowstorm crowing its peak: Mount Everest.

My friend and I looked at each other, then started shouting and jumping up and down. Energy raged through my body, chasing away my dejection, as feelings of euphoria, freedom, and victory poured through me. I felt amazing! We stopped jumping, collected ourselves, then gave each other a big hug. Our situation sank in. Yes, we had been caught by the Chinese police, but we had just completed an epic trip through one of the most difficult and beautiful countries in the world. This vista before us was like an award, a diploma acknowledging that. We had made it!

Standing there with that view, the clear blue sky in the background of those awe-inspiring mountains, I could feel the seed that had been planted inside of me. Meeting those gentle, silent people that were so intuitive and wise, who knew how to live so simply, had touched something deep within me. A desire for more travel and for meeting different people had been born. I knew there was more for me out there, I just didn’t know exactly what. My call to travel came from a deep place—to learn things, to see places, and to meet people, but it was more than that. I felt called to seek out something deeper in life—something I always felt was possible. Looking back now, I understand why I felt the call to travel since a very young age: I was looking for home.

Below are graphic pictures of a Tibetan Sky Burial, please view respectfully, and with caution

Hello Dennis. Deep bow to you and your being. Thank you for sharing your ncredible trip through Nepal into Tibet.. your pursuit of your intentions that took you into Tibet and the incredible synchronicities that flowed through you, the people around and the land. Everything aligned for you in the most perfect way and time.

I have always been drawn to Tibet as well.. and to other ancient places before they get lost to modern civilization. Reading your post reminded me of my own passion and deep call to authentic travel.. which has been buried these days as I am consumed in my current form of life.. not complaining though as I am relishing every moment right now as a mother of a 6 month old.. I am hopeful that at the right time I will be back on the road again.

Deep gratitude to you for sharing. Deep deep gratitude for initiating me into the journey of medicine.

Aho

Shaeesta

In tears